Bill Gates and the Greatest Tech Hack Ever

Bill Gates has pulled off one of the greatest hacks in technology and business history, by turning Microsoft’s success into a force for social responsibility. Imagine imposing a tax on every corporation in the developed world, collecting $100 per white-collar worker per year, and then directing one third of the proceeds to curing AIDS and malaria. That, effectively, is what Bill Gates has done.

On a day when everyone will be noting Gates’ departure from day-to-day involvement in his work at Microsoft, it’s worth noting the work he’s done which will likely be seen as his greatest legacy.

The unofficial goal of Microsoft in its early years was to see a computer on every desk and in every home, presumably running Microsoft software. That sort of vision, put forth in a time when the conventional wisdom dictated that personal computers might disappear entirely, was astounding enough. But by the year 2000, just 25 years after its founding, Microsoft had achieved that improbable goal, at least in the developed world.

The story of the Gates Foundation is well-covered, but it’s important to consider the context in which the Foundation was created. What would you do if you defined the most ambitious goal you could imagine, and then achieved it just 25 years later? And what if you had done so while still relatively young, not even fifty years old? That’s the position Gates found himself in just a decade ago.

Most people, when faced with the realization of their greatest dreams, will respond at first with elation, and then later settle into melancholy or even depression. It can be overwhelming to think that there’s nothing left to do. Instead, Gates upped the ante.

How high did he set his new goals? How about curing AIDS? Or ending the spread of malaria? What about improving life expectancy and quality of life for the poorest people in the world? After achieving a goal that seemed outlandish, it’s clear that the only logical next step is to try to achieve a goal that seems nearly impossible. I have to point out that sense of thinking “Okay, we won — what next?” is extremely unusual.

Plainly, I admire Bill Gates for this. I think there are few people who, instead of resting on their laurels, decide to stake their reputation and fortune on goals that are not only altruistic, but that conventional wisdom dictates may not be achievable in a single lifetime. There are many other ways to measure a man, and I’m not diminishing at all the fact that Microsoft as a corporation has made regrettable, unfortunate, and even illegal decisions during Bill Gates’ tenure. But imagine if someone had defined an explicit goal of a “cure AIDS tax” for corporations, and then tried to get that enacted. The fact that, effectively, this has happened is remarkable.

And there are many who still want to think, despite the commitment of incredible resources and formidable talents to support the Gates Foundation’s mission, that all of this philanthropic work is an attempt to simply generate good PR. But that simply doesn’t follow the facts.

A Family Tradition

The truth is, Bill Gates doesn’t just come from a family tradition of philanthropy: It’s actually a significant part of the reason he got the single biggest opportunity of his professional career. You can see the family tradition today, with the founding chairman of the Gates Foundation being William Gates Sr., Bill’s father. But you have to go back twenty years earlier, to Gates’ mother Mary Maxwell Gates, to understand how philanthropic work opened doors for a fledgling Bill Gates and Microsoft.

Mary Maxwell Gates was deeply involved in the work of the United Way for many years before her passing in 1994, most notably as its first female chair. And one of the connections she made through that work back in 1980 was to John Opel, the chairman of IBM who was also a member of the United Way’s executive committee.

It’s become fairly clear in the years since that at least part of the reason IBM was willing to hire Microsoft to create an operating system for the initial release of the IBM PC was because of the introductions made through that connection. Taking a risk on an unproven small software company was a big leap to take, and it’s one that ended up being the greatest turning point in the history of the biggest software company that’s ever been created.

It’s fitting, then, that that opportunity is honored by having the founder of the company return all of his efforts and the vast majority of his wealth to an even more ambitious new vision for philanthropic work. So, congratulations to Bill Gates on his new job, and I hope this hack is even more successful than all the ones that he’s done in the past.

Essential Links

A few recommendations for those who want to understand more about Bill Gates and his legacy:

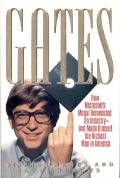

- Stephen Manes and Paul Andrews published Gates: How Mirosoft’s Mogul Reinvented an Industry, back in 1992. I have been a big fan of this book since it came out. It was released before his period of greatest fame after Windows 95 launched, and perhaps as a result is more insightful than later efforts that tried to case Gates’ entire life and career merely in the context of post-monopoly Microsoft. (I’ve shown the original, gloriously awful, cover photo above, but I think the paperback edition has less floppy-disk lunacy.)

- Fortune has a slideshow covering 30 years of Bill Gates’ career, narrated by the man himself.

- Gates’ 2003 rant about the shoddiness of the Windows user experience. Though this has prompted lots of “haw, haw, Windows sucks!” responses from geeks, I though it was interesting to look past the memo as merely a document of a typically dysfunctional large company. What struck me was a founder, nearly 30 years after starting the company, and decades after becoming wealthy beyond his wildest dreams, still obviously had both great passion and an enormous amount of technical knowledge.

- Those same themes of passion and technical competence are echoed in Joel Spolsky’s essay about his first BillG review. Joel revisited this in a less-geeky version of the essay published in Inc. magazine.